For many people across the world, religion plays an important part in their daily lives and identities. While others lead happy lives without believing in a god(s). Why do some of us feel the ‘need to believe’?

Do humans | need religion?

Some people argue that we need religion to be moral - to give us a sense of right and wrong, and help us be ‘good’. It sets a standard for good behaviour and punishes the bad. Others would say that it is perfectly possible to be moral and happy without believing in God or gods.

What do we mean by good?

Dr Oliver Scott Curry, a Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropologist at the University of Oxford, explains that there’s quite a long list of things that make up what we call ‘good’.

“Morality is all about cooperation - promoting the common good. Because there are many different types of cooperation, there are many different types of morality, including: sympathy, loyalty, reciprocity, bravery, respect, fairness and property rights.”

Do we need religion to behave well?

Human behaviour, both good and bad, is a product of nature and nurture.

“Millions of years evolution have equipped us with a range of social, cooperative and altruistic dispositions.,” says Dr Curry. “We’re hard-wired in our brains to be good to each other. We’re not angels but we’re not devils either.”

"How we behave is also influenced by our environments - how we’re brought up, the people around us and what kind of culture we live in. For example, people compete for status in lots of different ways in different cultures. In some societies, people compete to eat the most hallucinogenic herbs, catch the biggest fish, kill the most enemies, write the best poem…in others, people compete by being the most generous, most brave, or most helpful.”

What is the connection between religion and morality?

There isn’t any necessary connection between religion and morality. “Morality is a lot older than religion. We’ve been moral beings for many years before we were religious. And, arguably, some religions aren’t moral at all. So, for example, some cultures have a belief in mischievous or even bad spirits. And humans have to make sacrifices and worship these bad spirits in the hope that they don’t do negative things to them e.g. ruin their crops or strike them down with a horrible illness.

“We’re used to the idea of powerful gods in the sky looking out for us and telling us to be good. That’s the basis of Christianity, Islam and Judaism. But these are relatively recent religions in terms of the history of human development. And even today not all religions follow the standard model of one kindly god looking out for us. Buddhism, for example, does not follow that model. Humans may have always had some supernatural belief but it hasn’t always been, and doesn’t have to be, moral.”

Codes of conduct

There’s a universal common moral code that nearly all societies tap into irrespective of religion or where they are in the world (Curry, O.S., Mullins, D.A. & Whitehouse, H., 2018).

“We recently conducted a large study of morals of 60 cultures around the world. We found that cooperation was key - and that cooperative behaviours formed the basis of seven universal moral rules. These are: help your family, help your group, return favours, be brave, respect authority, be fair and respect other people’s property".

“In some cultures, morality is wrapped up in a supernatural, mystical cloud. But this isn’t necessary for these moral rules to apply. Instead, myths and superstitions grow up around the moral code. They then become entwined with each other which is how we end up thinking religion equals morality. It may well do but we shouldn’t assume that it has to be that way” adds Dr Curry.

Are religious countries more moral?

It’s a common assumption that a country which is very religious will also be more law-abiding, moral and respectful than one which is not. But this is not the case.

According to the non-profit organization, Vision of Humanity, which publishes an annual Global Peace Index, the ten safest and most peaceful nations in the world are the least God-believing. While the least safe and peaceful nations are the most religious. This doesn’t mean that a lack of religious belief causes improved wellbeing or religious belief causes social problems. But it might mean social problems – a lack of basic necessities, and institutions like the rule of law – people might turn to religion out of desperation, explains Dr Curry. And once their situation improves, they may no longer put their faith in religion. “For example, once medicine came along and hospitals were built, people were much less likely to believe in magical potions and healing spells.”

“What’s clear from the research is that secular, non-religious countries, like the UK, are not negatively affected by the absence of faith,” says Dr Curry.

Do humans need faith to make sense of their lives?

So we’ve read that religion doesn’t necessarily make a country or culture moral or good. But what else could religion mean for humans? Does it offer a way to make sense of our lives?

“One of the things people get most meaning from is taking part in something collective, i.e. working with other people to achieve something together. We are social animals so that’s not really surprising. Your social network is your life support system. If you asked a bee what gives its life meaning, it would likely say working together with other bees to achieve something for all of them. It’s the same for us. Commitment to a cause greater than ourselves gives our lives meaning and makes us feel good,” says Dr Curry.

We like being in groups and it can be but doesn’t have to be, religious. For example, you could enjoy being a football fan or following a band, political party, theatre group or environmental campaign. All of these have the same thing in common - they bring people together and make you feel part of something bigger than yourself. That gives a warm glow and sense of belonging. And we humans need to feel we belong. It’s a great comfort knowing others feel the same way. You can get that from religion. But you can also get it from a wide variety of other forms of association and other beliefs.

Are there any groups you belong to that are important to you? Why do you think religion means so much to some people and groups, and not to others?

To read a summary of Dr Curry's research into morality across the world.

Gods and Lawyers

Dr Philippa Byrne (University of Oxford) discusses three fascinating questions: what's the difference between a religious teaching and a legal ruling? would we want religion to be a part of the law? and what happens when religion and law come into conflict?

Can football be a religion? The ‘Iglesia Maradoniana’ (Church of Maradona) was set up by fans of the Argentinian footballer, Diego Maradona. The church has its own set of commandments, including the instruction that all worshippers should take ‘Diego’

Can football be a religion? The ‘Iglesia Maradoniana’ (Church of Maradona) was set up by fans of the Argentinian footballer, Diego Maradona. The church has its own set of commandments, including the instruction that all worshippers should take ‘Diego’ as their middle name.

Are we programmed to believe in a superpower?

When we’re little, we think our parents know everything. If we’re sick, they always know just what’s wrong. If we’ve done something bad, they always seem to find out. And apparently they can even see inside locked boxes... at least, that’s what most three-year-olds seem to think...

When researchers at the University of Oxford asked three-year olds if their mum would know the contents of a locked box that she’d never seen before, they all said yes. They also believed that a supernatural being (like a god) would be able to know what was in the box. But when the researchers asked four- and five-year-olds, they weren’t so convinced about their mum’s superpowers. However, lots of them still thought that a god-type being would know what was in the locked box without ever having been near it.

So even once kids grow out of thinking that their mums are all-seeing and all-knowing, they still don’t have a problem with the idea that another being might be. Basically, they don’t seem to think there’s much that’s super about the supernatural - they find it much easier and more normal than a lot of adults to believe in things they can’t see or understand.

So does that mean that belief in a god or gods is a natural state for human beings? Or do we create our belief systems based entirely on our environment, the beliefs of those around us and the experiences of our everyday lives?

God on the brain

That’s pretty much exactly what a team of Oxford University researchers have tried to find out.

The researchers spent three years talking to thousands of adults and children in 20 different countries, looking at both religious and atheist societies. And they found that huge numbers of people across many different cultures instinctively accept the idea of gods and the supernatural and believe that some part of their mind, soul or spirit keeps on existing even after death.

Roger Trigg, an Oxford professor working on the project, said that their research showed that religion “wasn’t just something for a peculiar few to do on Sundays instead of playing golf. We’ve gathered evidence that suggests that religion is a common fact of human nature across different societies.” He thinks this makes it unlikely that religion will ever die out, adding that “attempts to suppress religion are likely to be short-lived, as human thought seems to be rooted to religious concepts.”

“Just because we find it easier to think in a particular way doesn’t mean that it’s true.”

Does our belief make God real?

But this doesn’t necessarily help us to know whether or not a god exists. Another Oxford researcher on the project, Dr Justin Barrett, said: “Just because we find it easier to think in a particular way doesn’t mean that it’s true.” So although the project has helped us to discover more about how natural belief seems to be for humans, it doesn’t necessarily mean that a god or gods actually exist – just that we seem programmed to think that they do.

In fact, some of the information the researchers found makes it seem as though believing in the supernatural is less to do with a god and more to do with us. For example, they discovered that people living in cities in more developed countries (places that have a higher standard of living, a stronger economy and better technology and trade) were less likely to have religious beliefs than people who lived in more rural areas. Dr Barrett says: “Individuals bound by religious ties might be more likely to cooperate as societies. We found that religion is less likely to thrive in cities where there is already a strong social support network.”

This suggests that faith might not just be about the thing you believe in, but also about what the thing you believe in can help you to accomplish. Often people find that when they’re united by something, even as small as a shared love of superhero comic books or banana milkshakes, it can help them get along better and work together more easily. So if the thing that unites people is as significant as belief in a god or a supernatural power, that can mean that living and working together as a society is a lot simpler because you share so many of the same values, ideas and goals. Some people would definitely find that a good motivator for belief.

So it seems like both nature and nurture have a part to play in faith and a belief in the supernatural. But does that help us get closer to the truth about whether or not a god exists? That’s for you to decide.

Going to extremes

A big concern for many people in the 21st century is that religious belief can fuel extremism and violence. If religion drives people to extreme action, should we be more critical of it? This video looks at the complex links between extremism, religion, politics and culture.

Power

1. Rock relief, Naqš-e Rostam, Iran, 3rd century AD

This monumental rock carving shows two riders on horses, both trampling enemies underfoot. On closer inspection, the figure on the left turns out to be the new Persian king, Ardashir I (224-42 AD), while the right-hand figure is the god Ohrmazd. The king’s horse crushes the body of his predecessor, just as the god triumphs over an evil spirit. The central focus of the whole image is a ring passed from god to king as if bestowing the right to rule. The carving communicates that Ardashir enjoys divine favour. What could be a more powerful way for the king and his new dynasty to get their message across?

Image: © Rachel Wood

Text: Katherine Cross

Storytelling

2. Franks Casket (front), probably Northumbria, early 8th century AD

This whalebone box presents a bizarre contrast. On the right you see the three Wise Men bringing gold, frankincense and myrrh to the infant Christ and the Virgin Mary. The left-hand scene, from a northern European myth, shows a magical blacksmith called Weland wreaking a bloody revenge. He is passing a drugged drink to his captor’s daughter, while her brother’s headless body lies at his feet. Why pair these scenes? Perhaps the contrast emphasizes the peace and order brought by Christianity. But maybe the two images are equals: the visit of the Wise Men to the baby Jesus is just another story to tell.

Image: © Trustees of the British Museum

Text: Katherine Cross

Morality

3. Parochet, Northern Italy (probably Venice), 1676

A parochet is a curtain that covers the Ark (chamber) which contains the holy Torah scrolls in a Jewish synagogue. It creates a physical barrier between the human realm and that of divine truth, and communicates that believers are in the presence of holy mysteries. This parochet is beautifully decorated: embroidered flowers flourish around symbols of Jewish worship. In the centre are the Ten Commandments, which God handed down to Moses on two stone tablets. These form the basis of a moral code for people to live by, providing a clear sense of right and wrong. The community who worshipped at this synagogue would have been reminded of these lessons whenever they saw their parochet.

Image: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Text: Maya Corry

Life-cycle

4. Carved figure of a woman breastfeeding, West Africa, 1890-1920

This statue probably represents Odudua, an earth goddess revered by the Yoruba people of West Africa. Her face shows the marks of deliberate scarring (a sign of great beauty) and she wears fine jewellery. The statue is carved from solid ebony, and the artist depicts Odudua as a powerful, maternal figure. The Yoruba believe that she helps to guarantee fertility, safe pregnancy and the birth of a healthy child. Many religions use ceremonies and works of art to mark key moments in the life-cycle: birth, the end of childhood, marriage and death. These rituals and objects provide structure to life, create bonds within a community, and help people to make sense of transitions and feel protected.

Image: Science Museum, London

Text: Maya Corry

Hope

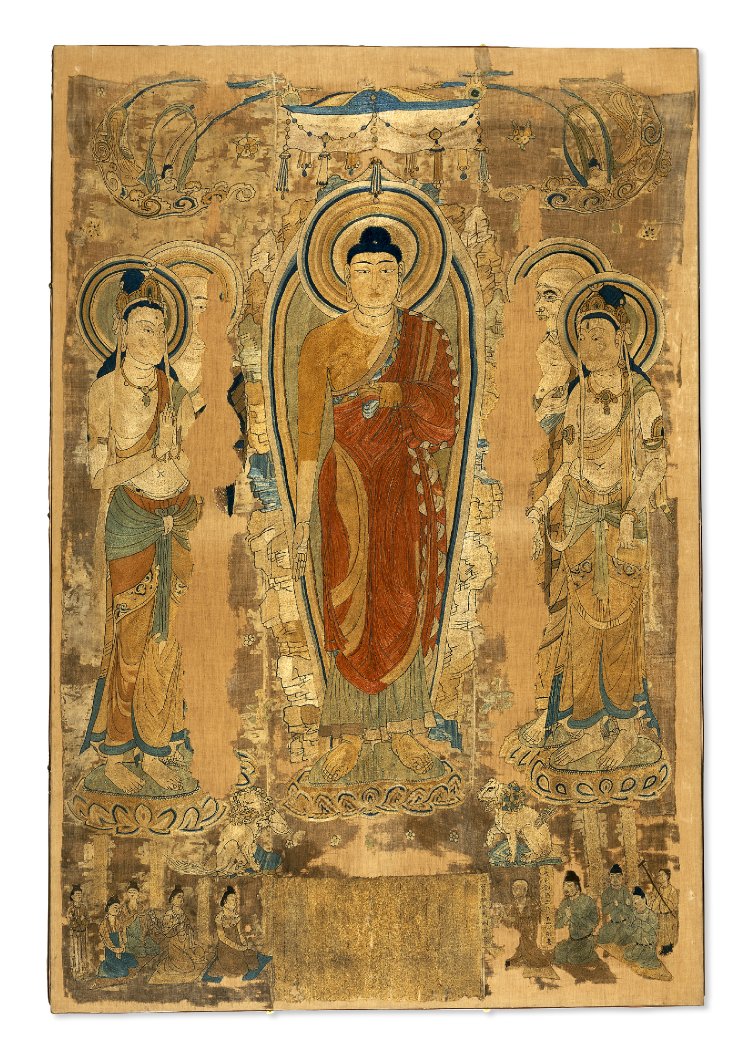

5. Śākyamuni preaching on the Vulture Peak, embroidery, China, 8th century AD

Although Buddhism is founded on the teachings of one man, the religion’s followers believe that everybody has the potential to attain the state of Buddhahood (enlightenment). This beautiful embroidery shows Śākyamuni Buddha, a spiritual teacher, preaching to his followers. Beneath him, little men and women are kneeling. They represent the family who paid for the embroidery to be made. By doing so, and by including their portraits within it, they hoped to gain blessings that would secure them a good reincarnation, moving them closer to nirvana. The image represents a hopeful philosophy: those who lived well and according to the teachings of the Śākyamuni Buddha could look forward to reincarnation, and need not fear death.

Image: © Trustees of the British Museum

Text: Maya Corry

Protection

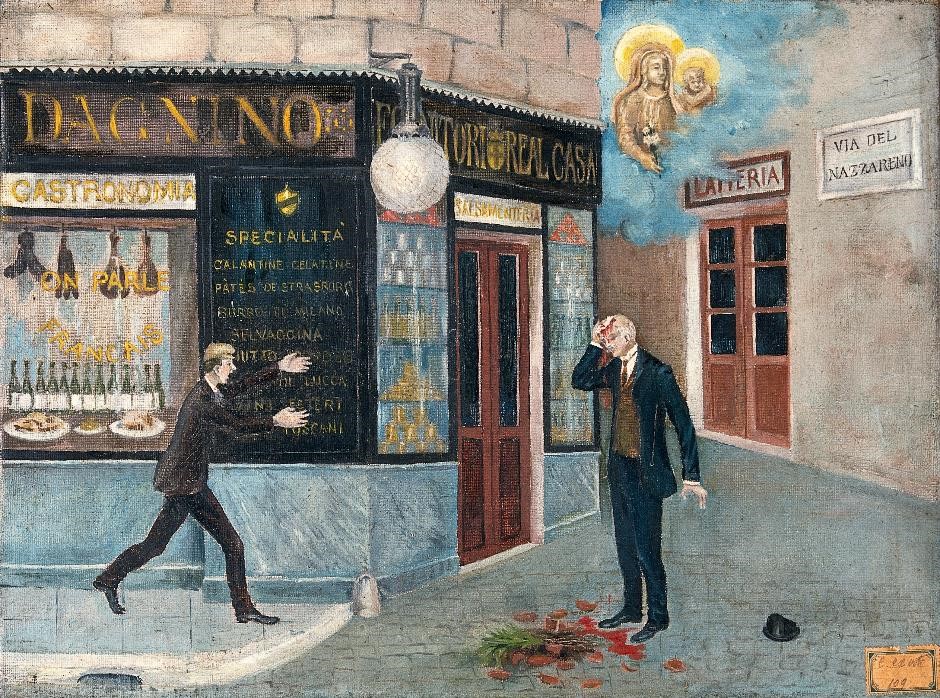

6. Ex-voto, Italy, c. 1890

An ex-voto is a gift left at a shrine in thanks for divine attention. This one shows a man in Rome who has been hit on the head by a falling flower-pot! Luckily, the Madonna and Christ Child (who we see hovering in the sky above him) have protected him from serious harm. For centuries Catholics around the world have produced ex-votos to show their gratitude for the miraculous interventions of holy figures in their lives. Many ex-votos refer to healings from sickness or accidents. In a world that can feel dangerous and uncertain, it is comforting to believe that you can face the trials of everyday life with divine help and protection.

Image: © Wellcome Collection

Text: Maya Corry

Celebrity worship

-

Tom Cruise

-

Scientology is a set of beliefs – including the belief in an alien overlord called Xenu – developed by the American science-fiction writer, L. Ron Hubbard. Like in other religions, Scientologists believe that you are essentially a spiritual entity that can survive the death of your body. The Church of Scientology has been and continues to be a controversial organisation. For example, it wages a campaign against psychiatry, denouncing it as unscientific. Joining the Church of Scientology involves signing a legal contract promising not to leave the organisation for one billion years and giving large financial donations. Its most famous member is the American film star, Tom Cruise. He joined in 1990 and has since made some pretty remarkable statements. He claims, for example, that Scientology cured his dyslexia because “we are the authorities on the mind, we are the authorities on improving conditions.” Once you've joined Scientology, the Church makes it extremely difficult for you to leave. For that reason, many European governments have labelled it as a cult. Cruise himself is known to have tried to charm the governments of countries where Scientology is in legal trouble.

-

-

Madonna

-

In the late 1990s, pop star Madonna joined the Kabbalah Center in Los Angeles. Kabbalah is an ancient esoteric branch of Judaism that focuses on the mystical interpretation of the Bible. The Kabbalah Centre attempts to show how these mystical teachings have a universal spiritual significance that can be applied in everyday life. For example, it suggests that the five senses only allow us to experience about 1% of reality. Imagine that! Madonna embraced this New Age version of Kabballah: “All the puzzle pieces began to fall into place,” she said in 2009. “Life no longer seemed like a series of random events. I started to see patterns in my life. I woke up.” She started wearing the signature red string bracelet - protecting against people with ‘an evil eye’ - and she adopted the Hebrew name, Esther. It also influenced her music, in particular, the album Ray of Light. Her 2012 Super Bowl Halftime Show was similarly full of esoteric symbolism: for example, the stage displayed a huge piercing eye, as well as a winged sun-disk used by ancient Egyptian mystics. Less subtly, she performed wearing a shirt saying ‘Kabbalists Do It Better’ during one of her world tours. However, some Jewish scholars accuse Madonna of distorting and commercialising Kabbalah. This is sometimes referred to as cultural appropriation i.e. taking a symbol from a different culture and using it for your own aims which, in doing so, might mean the symbol loses some of its original meaning. What do you think?

-

-

Orlando Bloom

-

Starring in blockbuster franchises like Lord of the Rings and Pirates of the Caribbean, actor Orlando Bloom felt he needed some peace and quiet in his life. For that reason, he converted to Buddhism during a ceremony at the Soka Gakkai International Centre in Britain in 2004. Soka Gakkai International is a Lay-Buddhist organisation. This means that - unlike the image some may have of Buddhists - Bloom does not live in a monastery. He is still a member of society and will hopefully make many more films! He has told interviewers that Buddhism ultimately supplies “an unshakeable sense of self.” Because of that, Bloom confesses that “it’s been a real anchor for me.”

-

-

Zayn Malik

-

The London Evening Standard recently identified pop star Zayn Malik as “the most high-profile British Muslim in the entertainment industry.” Though he’s not currently practising, he was nevertheless raised within the Islamic faith. For that reason, he says he identifies strongly with Islamic culture. Malik is very aware of how important it is to have people of different backgrounds in the public eye. This might explain why he says he takes “a great sense of pride – and responsibility – in knowing that I am the first of my kind, from my background.” By this he means that he is one of the first people of British Muslim heritage to become as famous as he is. Nevertheless, he wants people to know that there’s more to him than his religion.

-

-

Stephen Fry

-

Stephen Fry identifies as a humanist. Humanism is a set of beliefs that have the human being - not God - at its centre. The human being can on their own - through reason and science - understand what the world is and what they are supposed to do in the course of their lives. When interviewed on Irish television in 2015, Fry said that he would have no respect for an “utterly evil… capricious, mean-minded… god that creates a world that is so full of injustice and pain”. Therefore, Fry says, “the moment you banish him, your life becomes simpler, purer, cleaner, more worth living.” Some critics would argue that the problem of why God permits the existence of evil has been central to theology and philosophy for centuries. It even occupies its own branch of reflection called theodicy. The 17th century German philosopher and mathematician, Gottfried Leibniz, for example, believed that this is the best possible world. There might still be a bit of evil in it, but God could not have created a better one. What do you think?

-

-

Martin Luther King Jr.

-

Martin Luther King Jr. was not only an American civil rights activist, but also a Christian priest and academic theologian. For him, political activism was a direct continuation of his call to the Christian ministry. King’s emphasis on nonviolence in protests - inspired by Mahatma Gandhi - has its roots in Biblical instructions like turning the other cheek when wronged. For King, the Gospels also carry a deep social message. He is recorded to have said that “we must move into a sometimes hostile world armed with the revolutionary Gospel of Jesus Christ. With this powerful Gospel, we shall boldly challenge the status quo.” By this, King means that Christians should constantly try to improve society and make the world a better place for everyone. To him, the Gospel was revolutionary; its message had the power to fundamentally change society.

-

-

Stormzy

-

On the cover of his debut album, Gangs, Signs & Prayer, the British rapper Stormzy takes the place of Jesus in a scene very similar to depictions of the last supper (but with more Balaclavas!). Rather than trying to make fun of religion, Stormzy is referring to his own beliefs. Indeed, he stands in a long tradition of Christian rap but is the first to achieve mainstream success with it. In November 2017, his Christian-inspired single 'Blinded By Your Grace' rose to number one in the charts. Stormzy has expressed surprise at his recent achievements. In an interview, he said that all he can do to explain his success is point to a higher power: “If it doesn’t add up, I give it to God. Me getting that No1 on the last day doesn’t add up. I give it to God.”

-

Do humans need religion?

-

Morality can develop without religion

There’s a universal common moral code that nearly all societies tap into irrespective of religion or where they are in the world (an idea suggested by Dr K. M. Keith, 2003).

Dr Oliver Scott Curry, a Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropologist at the University of Oxford, explains that: “We recently conducted a large study of morals of 60 cultures around the world. We found that cooperation was key - and that cooperative behaviours formed the basis of seven universal moral rules. These are: help your family, help your group, return favours, be brave, respect authority, be fair and respect other people’s property".

And so there isn’t any necessary connection between religion and morality. “Morality is a lot older than religion. We’ve been moral beings for many years before we were religious. And, arguably, some religions aren’t moral at all. So, for example, some cultures have a belief in mischievous or even bad spirits. And humans have to make sacrifices and worship these bad spirits in the hope that they don’t do negative things to them e.g. ruin their crops or strike them down with a horrible illness.

-

Being part of something bigger than ourselves

“One of the things people get most meaning from is taking part in something collective, i.e. working with other people to achieve something together. We are social animals so that’s not really surprising. Your social network is your life support system… Commitment to a cause greater than ourselves gives our lives meaning and makes us feel good,” says anthropologist, Dr Oliver Scott Curry (University of Oxford).

You can gain these positive effects and feelings from religion. But you can also get them from a wide variety of other forms of association and other beliefs.

-

Things can get complicated

Historian, Dr Philippa Byrne (University of Oxford) explains that: “The relationship between law and religion today… is often a complex one in modern societies. And there's a lot of controversy around how we protect religious beliefs but also how we protect other people from religious beliefs of others…The problem for lawyers and judges is what happens when a person's faith might be damaging another person's rights and how far we protect religion in an increasingly diverse society. For example, imagine a case with a strictly religious baker who refuses to bake a wedding cake for a gay couple… whose rights should be protected here?”

-

Religion can inspire

Across the world, religious belief has inspired great/classic works of art, music, poetry and architecture. Beyond personal meaning, it could be argued that religion has contributed to human culture, our understanding of key concepts such as power, morality and the cycle of life, and indeed how we’ve recorded the past through the arts and other forms of storytelling.