Earthquakes, volcanoes, wild weather, and rocks from space… the Earth can be a dramatic place! But human beings are a pretty resourceful lot, and we’ve been surviving natural disasters for thousands of years. How have they shaped our world, and how will we cope with them in the future?

Please be aware that this Big Question contains descriptions and images of injuries and deaths caused by disasters which may be disturbing to some readers.

Test your knowledge about disasters from history

Where did the deadliest blizzard in modern history take place?

The Iran Blizzard, which took place in February 1972, was the most deadly blizzard in modern recorded history. In some areas snow reached a depth of 26 feet, while several towns and villages were completely buried. The storm resulted in the deaths of around 4000 people.

In 2006, 19-year-old Matt Suter survived an unusual encounter with a natural disaster. Was he:

In 2006, Matt Suter survived being taken up and blown by a tornado for nearly 400m, or about the length of four American football fields. Matt was sheltering from the tornado in a mobile home trailer near Fordland, Missouri. He reported seeing the doors and windows of the trailer fly off, then losing consciousness. Matt woke up in a field 398m away, and now holds the Guinness World Record for the human being who has travelled the furthest within a tornado and survived.

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 caused the deaths of between 3% and 6% of the entire world’s population, and may have infected up to one-third of all human beings alive on the planet. Why was it known as the ‘Spanish Flu’?

The Influenza Pandemic broke out during World War I, when strict controls were placed on the media. This meant that the British government ordered British newspapers not to write too much about deaths in the UK, France and other allied countries. The same thing was happening in Germany. However, Spain was neutral in the war – which meant that both Allied and German newspapers could freely report on how many people were suffering there. This gave readers the impression that the disease had begun in Spain or had hit Spanish people the hardest, neither of which was true.

The most recent limnic eruption occurred in 1986. It’s a rare natural disaster which causes what?

In a limnic eruption, a mass of dissolved carbon dioxide suddenly erupts or explodes from a deep lake. It then forms an invisible gas cloud which can suffocate animals and people. For this to occur, the lake’s water must be nearly saturated with CO2 and the lake must be deep enough to have a cold lower layer and a warm upper layer. Limnic eruptions have been observed at Lake Monoun and Lake Nyos, both in Cameroon, while scientists believe that they may also occur at Lake Kivu, on the border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda.

When, where and why was the first seismoscope (instrument for detecting earthquakes) invented?

The first seismoscope (earthquake measuring device) was developed by Chinese mathematician and inventor Zhang Heng. It was a large bronze container with eight dragon heads around the outside. Each dragon head held a ball in its mouth, and any slight movement would cause it to fall, showing which direction the earthquake was coming from. Zhang Heng created the instrument so that the Emperor could quickly dispatch troops to an earthquake location in order to prevent disorder and rioting.

Between 1875 and 1878, India (as well as other countries) suffered a three-year-long drought and famine which led to the deaths of millions of people. Which of the following was NOT a major cause?

The Great Famine of 1876-78 had a number of causes. One problem was an unusually strong El Niño effect. This is a climate cycle in the Pacific Ocean which spreads warm water throughout the ocean, releasing extra heat into the air. Another system, the Indian Ocean Dipole, also weakened the annual monsoon rains: these factors combined to cause major droughts. However, the loss of life was exacerbated by the British colonial government’s policy of exporting food grown in India to England and forcing people to grow non-edible ‘cash crops’ such as indigo and cotton instead of food.

Disturbances to the climate after the eruption of Mount Tambora caused the year 1816 to be known as what?

When Mount Tambora erupted, it discharged enough volcanic ash, sulfur and water into the atmosphere to cause what is known as a ‘volcanic winter’. This is a temporary drop in the overall temperature of the Earth. As a result, the summer of 1816 saw frosts and snowfalls in the middle of June in parts of the USA. Failed crops led to famine in Wales and Ireland and disruptions to the monsoon season caused flooding in China. This caused 1816 to be called ‘The Year Without a Summer’.

In 1983, southeastern Australia suffered a terrible series of wildfires. Over 180 separate fires were reported on the same day. The event happened to take place on a holiday in the Christian religious calendar, so the fires became known as the…?

The fires took place on Wednesday 16th February 1983 – Ash Wednesday in the Christian calendar. The fire destroyed more than 3000 properties and hundreds of thousands of animals, more than 2,600 people were injured and 75 lost their lives.

According to the World Heath Organisation, a natural disaster is

"an act of nature of such magnitude as to create a catastrophic situation in which the day-to-day patterns of life are suddenly disrupted and people are plunged into helplessness and suffering, and, as a result, need food, clothing, shelter, medical and nursing care and other necessities of life, and protection against unfavourable environmental factors and conditions."

Guide to sanitation in natural disasters, WHO (1971).

This means that a natural disaster is

A) A natural event, that

B) Suddenly and seriously affects people's ability to go about their everyday lives.

As Oxford Geography DPhil student Liam Saddington points out, this means that a massive storm, drought, volcanic eruption, wildfire or meteorite strike that hits somewhere where no human beings are around to be affected is technically a "natural event", not a "natural disaster".

To learn more about the scientists who study natural events and disasters, read on!

Dr Brandon Hedrick: Palaeobiologist

Dr Brandon Hedrick researches palaeobiology… that’s the study of ancient life on Earth, including our favourite giant prehistoric beasties! He explains what scientists think happened to the dinosaurs, and how they solved the mystery of what could have made so many different species extinct at once.

Dr Rosie Jones: Volcanologist

Helicopter rides to Russian volcanoes, geology lessons with Granddad, and why you might start worrying if your local volcano ISN’T expelling volcanic gases – Dr Rosie Jones gives us the hot news (sorry) on life as a volcano scientist.

Dr Austin Elliott: Earthquake Geologist

Dr Austin Elliott studies the size, location, and characteristics of earthquakes that have already happened in order to assess the hazards of future ones. He tells us why this is important, and how scientists can help people plan to protect themselves.

Professor Manolis Chatzis: Earthquake Engineer

When he was 15, the future Professor Manolis Chatzis and his family survived a violent earthquake in their home city of Athens. Today he is an earthquake engineer, coming up with new ways to protect buildings (and the people and things inside them!) from seismic shaking and building collapse. He explains why designing buildings for earthquakes is a bit like building a car.

Anna Rufas Blanco: Oceanographer

Anna Rufas Blanco is writing her DPhil (PhD) on the Biological Carbon Pump – a system in the ocean that allows tiny plants and creatures to lock away carbon dioxide that would otherwise contribute to global warming. She explains how this works, and tells us what it takes to be an oceanographer.

Witnesses to disaster from Pompeii to Malibu

What do Miley Cyrus and Liam Hemsworth have in common with a Victorian sea captain, a medieval tax collector and a teenager from Ancient Rome? They’ve all been directly affected by natural disasters, and have lived to tell their stories.

Please be aware that some videos and images below contain detailed descriptions and footage of injuries and death which may be disturbing to some readers.

-

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79CE caused widespread destruction. Burning ash engulfed the nearby Roman cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae, burying them so deeply that they would not be re-discovered until the 1700s. A young man named Pliny, who would later grow up to be a lawyer and writer known as Pliny the Younger, was in the nearby town of Misenum. He was eighteen years old, and he wrote down what he saw:

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79CE caused widespread destruction. Burning ash engulfed the nearby Roman cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae, burying them so deeply that they would not be re-discovered until the 1700s. A young man named Pliny, who would later grow up to be a lawyer and writer known as Pliny the Younger, was in the nearby town of Misenum. He was eighteen years old, and he wrote down what he saw:'You might hear the shrieks of women, the screams of children, and the shouts of men; some calling for their children, others for their parents, others for their husbands, and seeking to recognise each other by the voices that replied; one lamenting his own fate, another that of his family; some wishing to die, from the very fear of dying; some lifting their hands to the gods; but the greater part convinced that there were now no gods at all, and that the final endless night of which we have heard had come upon the world... At last this dreadful darkness was dissipated by degrees, like a cloud or smoke; the real day returned, and even the sun shone out, though with a lurid light, like when an eclipse is coming on. Every object that presented itself to our eyes (which were extremely weakened) seemed changed, being covered deep with ashes as if with snow.'

From the British Museum's online exhibition 'Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum'.

-

The Great Plague, also known as the Black Plague and the Black Death, was a widespread and extremely dangerous illness. It was caused by a species of bacteria called Yersinia pestis, which was carried by fleas, and caused three separate strains of life-threatening illness. One attacked the body’s lymph system, one destroyed lung tissue and the third infected the blood. These three different strains with different symptoms made it particularly tricky to identify and treat. Most historians agree that in Europe between 30% and 60% of people died, although it’s difficult to know exact numbers. The disease reached its peak around 1347-51 but continued to exist in small pockets for centuries. Agnolo di Tura was an ordinary person - a shoemaker and tax collector who lived in Siena, Italy. His nickname was ‘Agnolo del Grasso’ or ‘Agnolo the Fat’. He spent his spare time writing historical stories, and included an account of his experiences during the epidemic:

'I do not know where to begin to tell of the cruelty and the pitiless ways. It seemed to almost everyone that one became stupefied by seeing the pain. And it is impossible for the human tongue to recount the awful thing. Indeed one who did not see such horribleness can be called blessed. And the victims died almost immediately. They would swell beneath their armpits and in their groins, and fall over dead while talking. Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another. And in many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead. And they died by the hundreds both day and night, and all were thrown in those ditches and covered over with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled more were dug. And I, Agnolo di Tura, called the Fat, buried my five children with my own hands. And there were also those who were so sparsely covered with earth that the dogs dragged them forth and devoured many bodies throughout the city. There was no one who wept for any death, for all awaited death. And so many died that all believed that it was the end of the world.'

from P. M. Rogers, Aspects of Western Civilization, Prentice Hall, 2000, pp. 353-365.

-

Maria Graham (later Lady Maria Callcott) was part of a Royal Navy family. She travelled around the world with her father, and later her husband, and wrote books about what she saw. She was in Chile during the earthquake of 1882, and the observations that she wrote down and published were later used by the geologist Charles Lyell to support the theory that earthquakes could cause land masses to rise. Maria wrote:

Maria Graham (later Lady Maria Callcott) was part of a Royal Navy family. She travelled around the world with her father, and later her husband, and wrote books about what she saw. She was in Chile during the earthquake of 1882, and the observations that she wrote down and published were later used by the geologist Charles Lyell to support the theory that earthquakes could cause land masses to rise. Maria wrote:'Never shall I forget the horrible sensation of that night… Amid the noise of the destruction before and around us, I heard the lowing of the cattle all the night through; and I heard too the screaming of the seafowl, which ceased not till morning. There was not a breath of air; yet the trees were so agitated that their topmost branches seemed on the point of touching the ground…

Great fissures are made on the banks of the lake; the house is not habitable; some of its inmates were thrown down by the shock, and others by the falling of various articles of furniture upon them… The alluvial soil on each side of the river looks like a sponge, it is so cracked and shaken: there are large rents along the sea-shore; and during the night the sea seems to have receded in an extraordinary manner.'

From Maria Graham, Journal of a Residence in Chile, During the Year 1822; and a voyage from Chile to Brazil in 1823.

-

In late August 1883, the small island of Krakatau (Krakatoa) in Indonesia was practically destroyed when its volcano erupted. The noise of the eruption was heard across over 10% of the globe, and the resulting tsunamis caused destruction to nearby islands and were felt as far away as South Africa. W.J. Watson was the captain of the Irish merchant ship the Charles Bal, which was caught in the volcanic cloud following the initial eruption. Captain Watson reported:

In late August 1883, the small island of Krakatau (Krakatoa) in Indonesia was practically destroyed when its volcano erupted. The noise of the eruption was heard across over 10% of the globe, and the resulting tsunamis caused destruction to nearby islands and were felt as far away as South Africa. W.J. Watson was the captain of the Irish merchant ship the Charles Bal, which was caught in the volcanic cloud following the initial eruption. Captain Watson reported:'Darkness spread over the sky, and a hail of pumice-stone fell on us, many pieces being of considerable size and quite warm. Had to cover up the skylights to save the glass…

The blinding fall of sand and stones, the intense blackness above and around us, broken only by the incessant glare of varied kinds of lightning, and the continued explosive roars of Krakatoa, made our situation a truly awful one. At 11pm, having stood off from the Java shore, wind strong from the south-west, the island, eleven miles distant, became more visible, chains of fire appearing to ascend and descend between the sky and it, while on the south west end there seemed to be a continued roll of balls of white fire…'

From letter published in Nature, Dec 3 1883

-

John Barrett was an editor at the San Francisco newspaper The Examiner during the earthquake of 1906. Large sections of the city were damaged not just by the tremor itself, but by buildings which caught fire after the quake and damage to the city’s water mains which made it impossible to put the fires out. More than 3000 people died and 250,000 were made homeless. John wrote:

John Barrett was an editor at the San Francisco newspaper The Examiner during the earthquake of 1906. Large sections of the city were damaged not just by the tremor itself, but by buildings which caught fire after the quake and damage to the city’s water mains which made it impossible to put the fires out. More than 3000 people died and 250,000 were made homeless. John wrote:'It was as if the earth was slipping gently from under our feet. Then came a sickening swaying of the earth that threw us flat upon our faces. We struggled in the street. We could not get on our feet. I looked in a dazed fashion around me. I saw for an instant the big buildings in what looked like a crazy dance. Then it seemed as though my head were split with the roar that crashed into my ears. Big buildings were crumbling as one might crush a biscuit in one’s hand. Great gray clouds of dust shot up with flying timbers, and storms of masonry rained into the street. Wild, high jangles of smashing glass cut a sharp note into the frightful roaring. Ahead of me a great cornice [part of a building] crushed a man as if he were a maggot… Everywhere men were on all fours in the street, like crawling bugs. Still the sickening, dreadful swaying of the earth continued… I saw trolley tracks uprooted, twisted fantastically. I saw wide wounds in the street. Water flooded out of one. A deadly odour of gas from a broken main swept out of the other. Telegraph poles were rocked like matches. A wild tangle of wires was in the street. Some of the wires wriggled and shot blue sparks. From the south of us, faint, but all too clear, came a horrible chorus of human cries of agony. Down there in a ramshackle section of the city the wretched houses had fallen in upon the sleeping families…'

From Louise Chipley Slavicek, The San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906, New York: Chelsea House, 2008.

-

On the Caribbean island of St Vincent, people still remember the eruption of the volcano La Soufrière on Good Friday, 1979. In the video below, they discuss what it was like to find out that the volcano was about to erupt. As you watch, consider again the differences between people, and how this might affect their memories of the event. This film was made in 2014, 35 years after the volcano erupted - how old would the people interviewed have been at the time of the eruption? How might this have affected the way they saw things?

This film was created as part of a workshop held on the island in 2014 by the STREVA (Strengthening Resilience in Volcanic Areas) project. This project works to predict and understand the risks faced by communities living near active volcanoes and support people in managing these risks.

-

A limnic eruption is a very rare natural disaster in which a body of water becomes saturated with CO2 gas which is then rapidly released. The gas forms a dense cloud which floats close to the earth and can suffocate people and animals. It is also known as ‘lake overturn’ or ‘exploding lake’. In August 1986, Lake Nyos in Cameroon experienced a limnic eruption – and around 1700 people and 3000 domestic animals were killed overnight.

After the disaster, the survivors were interviewed by a team of Peace Corps workers and anthropologists (people who study human cultures) in an effort to understand what had happened. One survivor was Mr Joseph Nkwain, who said:

'I was in Subum with my daughter who came to spend holidays with me. It was the evening [9.30 p.m] of the 21st and we were sitting at the table reading, trying to help my small daughter with her studies. Then she went to bed and fell asleep; I also went to bed without noticing any sign of anything… [During the night] I heard some sound, something sounded like an airplane... All of a sudden, my skin became very hot and I perceived something making some dry smell. I could not speak, I became unconscious, I could not open my mouth because then I smelt something terrible and could not speak. I just closed my mouth and remained silent. All of a sudden, I heard my daughter snoring in a terrible way, very abnormal. So I forced myself to stand up from the bed, I was already weak. I tried to see what was happening with my daughter and find out really what was smelling in the house. I did not really know what the smell was, the smell was terrible. So just when I stood up, I fell. When crossing to my daughter's bed, in the middle of the floor, I collapsed and fell. I fell, I remained there, I didn't stand up… I was there until a friend of mine came and knocked at my door… My daughter was already dead. I didn't know that she was dead, I thought she was still sleeping.'

From: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, Volume 51, Issues 1–2, June 1992, pages 171-184.

-

In 2011, a massive (9.0-9.1 magnitude) underwater earthquake off the coast of Japan triggered a tsunami. The waves reached heights of up to 40 metres, and more than 15,000 people died. The tsunami also triggered meltdowns at three nuclear reactors in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant complex. In this video, brother and sister Takuma and Sayaka Wakasugi, who lost their father in the tsunami, return to the site of their former home and discuss how they have coped with his loss.

-

In November 2018, two major wildfires in California destroyed hundreds of houses and businesses. At least 88 people had lost their lives at the time this Big Question was written (Source: California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, Camp Fire and Woolsey Fire datasheets). Among those who lost their homes were singer Miley Cyrus and actor Liam Hemsworth. But rather than complaining, the couple said that they were grateful that their loved ones and pets had been safely evacuated, and donated $500,000 to assist others who had lost their homes.

In November 2018, two major wildfires in California destroyed hundreds of houses and businesses. At least 88 people had lost their lives at the time this Big Question was written (Source: California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, Camp Fire and Woolsey Fire datasheets). Among those who lost their homes were singer Miley Cyrus and actor Liam Hemsworth. But rather than complaining, the couple said that they were grateful that their loved ones and pets had been safely evacuated, and donated $500,000 to assist others who had lost their homes.

What do you think? These accounts were created by many different people, who were writing/speaking with different purposes in mind. How do you think this might have influenced their point of view?

For example, Maria Graham and Captain W.J. Watson are keen to record their observations about changes in the environment following a disaster - how is this different to the way that Miley Cyrus or Agnolo di Tura write about their families? How might other aspects of these witnesses' identities have influenced their accounts?

Ann Elizabeth Hodges was the first known person in history to survive being hit by a meteorite. On November 30 1954 she was asleep on the sofa at her home in Oak Grove, Alabama when a fragment of a larger meteor fell through the roof of her house. She sustained severe bruising, but was able to walk away from the incident.

Natural Disasters in Numbers

Do more people die from volcanoes than from landslides or floods? Where in the world are the most people displaced by natural disasters? And just how much do natural disasters cost us worldwide?

Researchers at the Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development have compiled lots of data to help answer these questions...

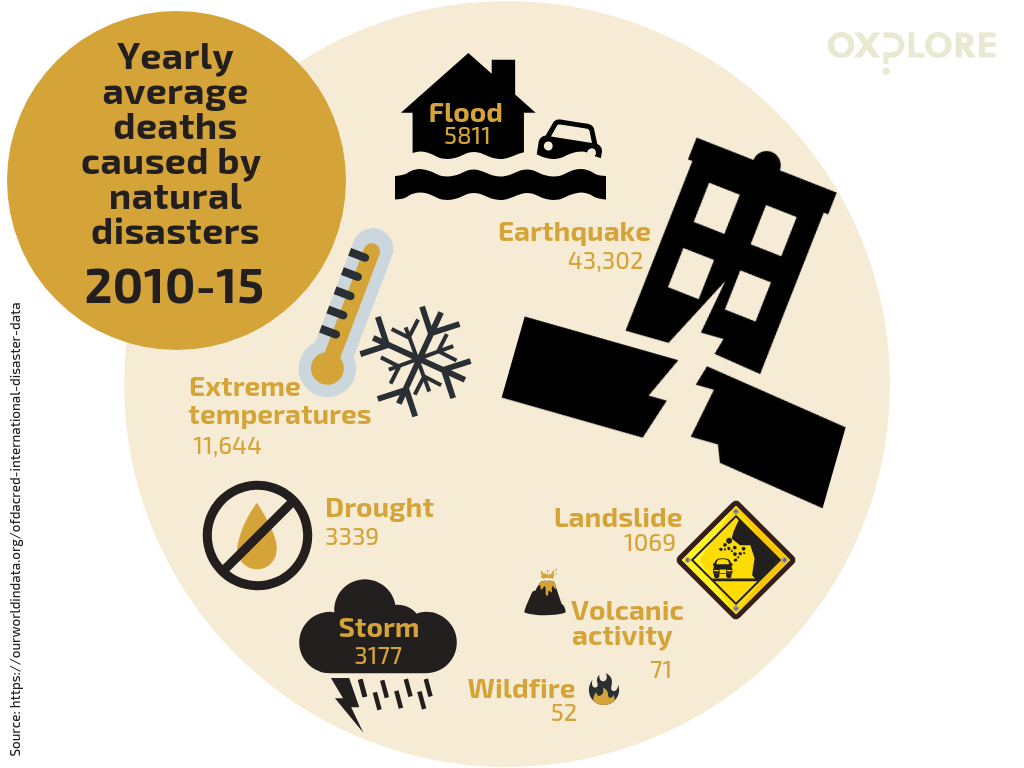

What are the most deadly natural disasters?

According to the OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database, yearly average death rates for different types of natural disasters in the years from 2010 to 2015 were:

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/ofdacred-international-disaster-data

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/ofdacred-international-disaster-data

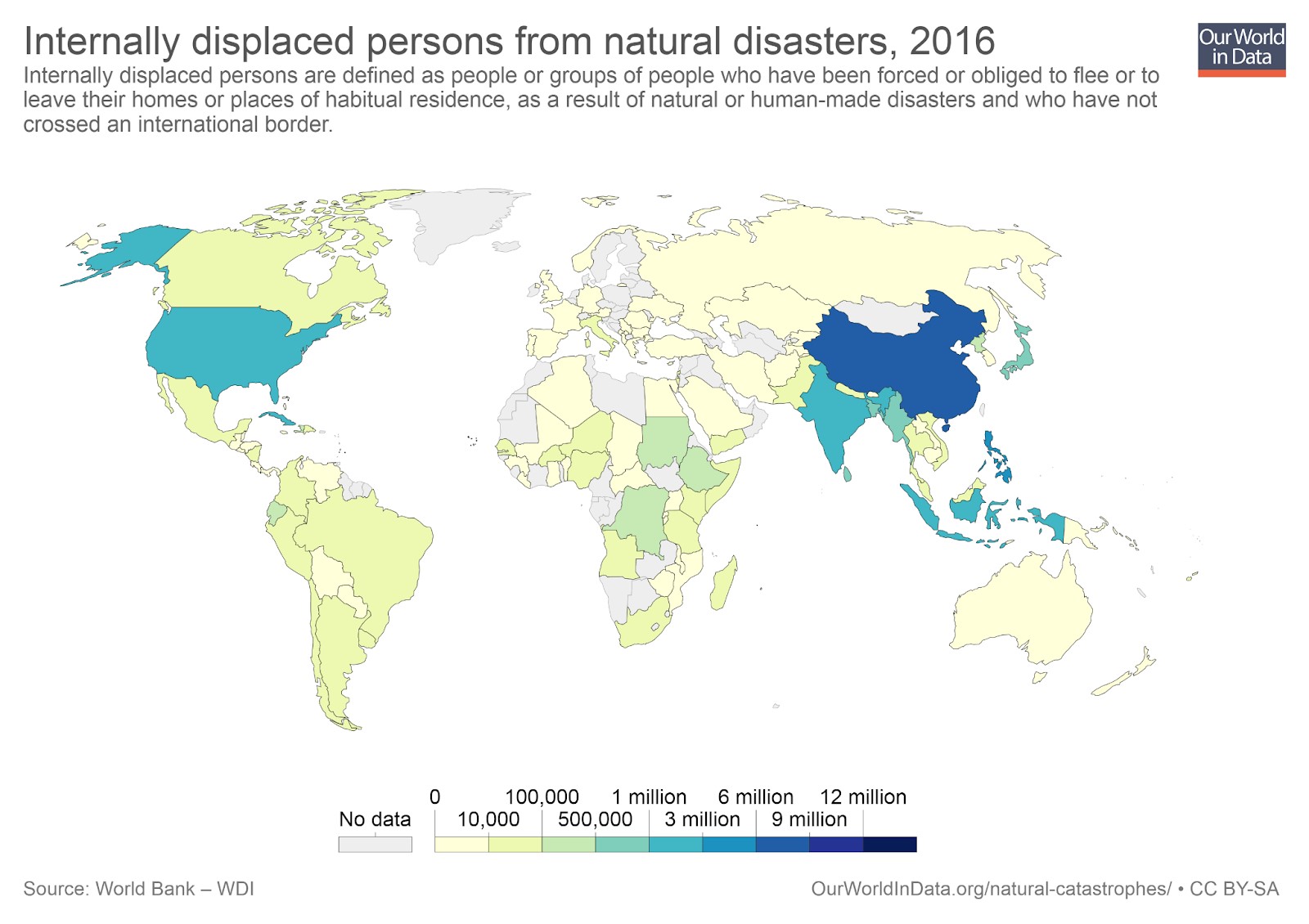

Who has to leave home because of disasters?

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/ofdacred-international-disaster-data

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/ofdacred-international-disaster-data

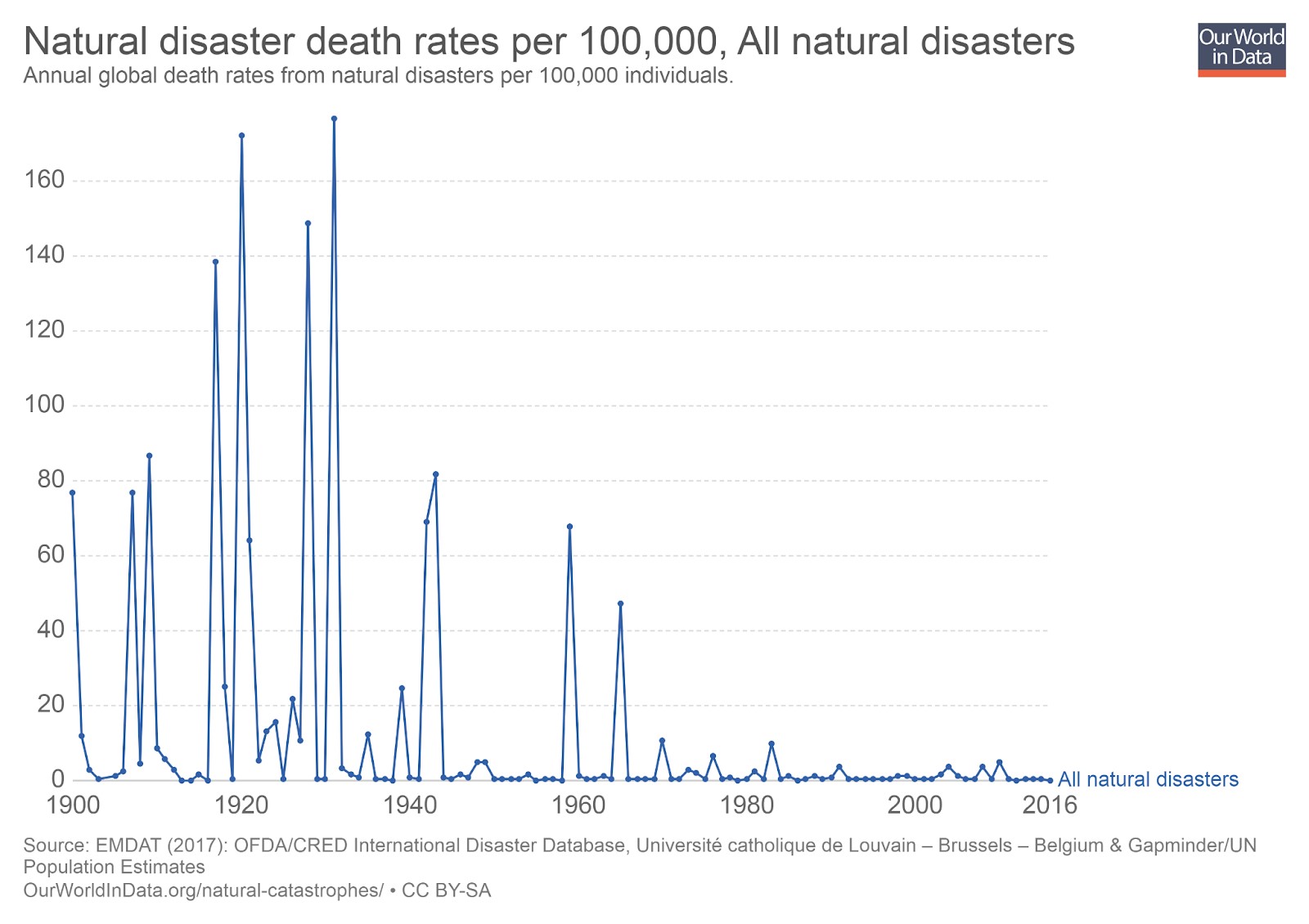

Are more or fewer people dying from natural disasters?

Don't forget: This graph shows deaths per 100,000 people, rather than absolute numbers of deaths. Source: https://ourworldindata.org/natural-catastrophes

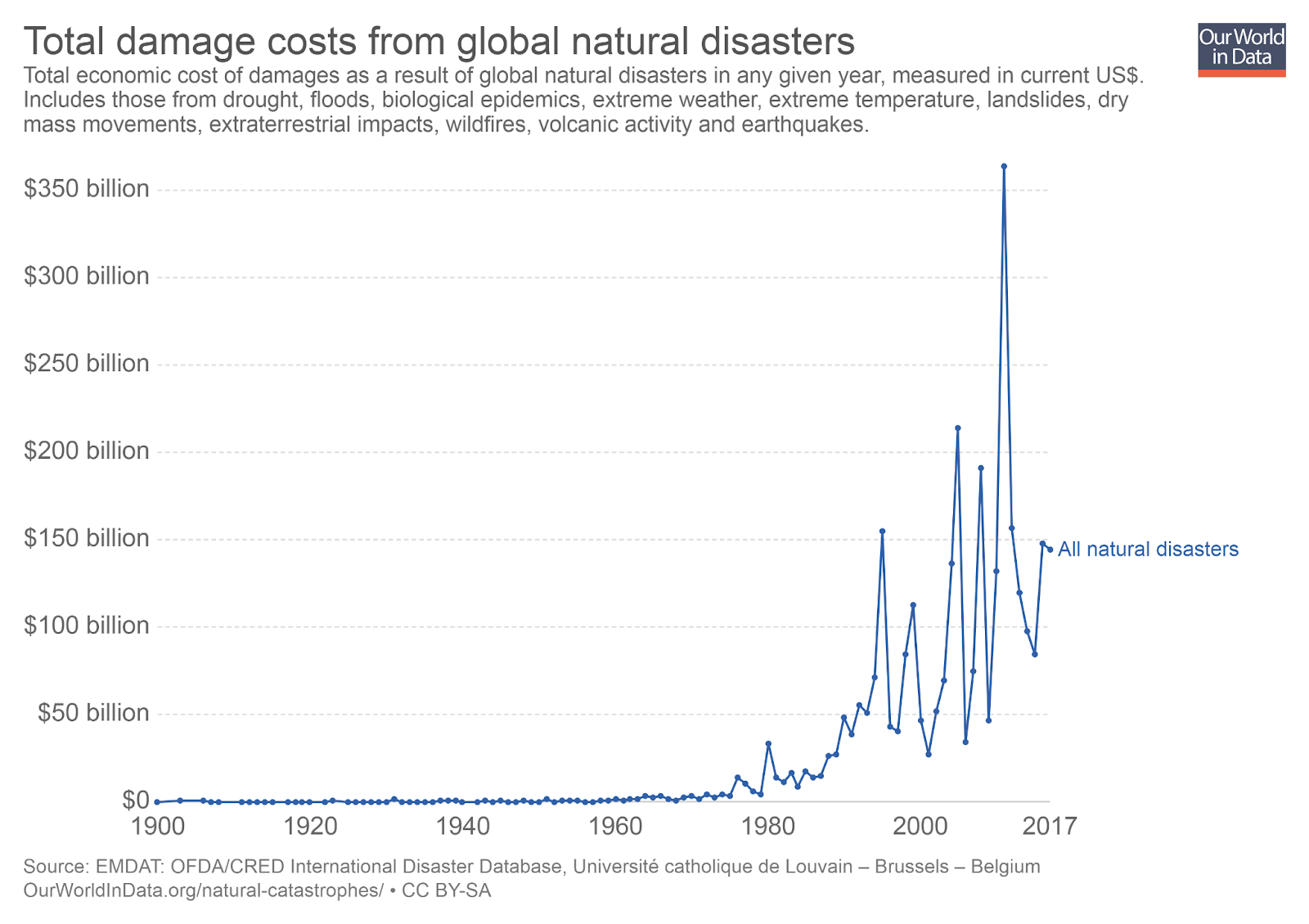

Are disasters getting more expensive?

In 1920, the poet Robert Frost wrote a poem called ‘Fire and Ice’ (we can’t reproduce it here, but it’s in lots of English textbooks!). In it, the poet seems to debate with himself about whether the world will be destroyed by fire or come to an icy, frozen end. But was Frost really writing about the literal end of the world, or was he using it as a metaphor, a way of talking about something else? Dr Erica McAlpine, who researches and teaches English Literature at St Edmund Hall, investigates further:

What do you think? If you were writing a poem about the end of the world, how would you imagine it? Could you use your imaginary disaster as a way of talking about a person's inner state of mind?

5 Innovations Inspired by Natural Disasters

-

Many public parks in Tokyo are specially designed to serve as emergency camping sites in case of disaster. If an earthquake or tsunami strikes, they can provide water reservoirs, emergency food supplies and toilet facilities. Some ‘Disaster Prevention Parks’ feature emergency command centres for officials, park benches that double as cooking stoves and even solar-powered lamp posts that can charge mobile phones. Learn more.

-

The LuminAID is an inflatable solar-powered lamp that folds down small and flat when not in use. Architecture students Anna Stork and Andrea Sreshta designed it after they learned about the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Since then, it has been distributed to disaster survivors in Nepal, Malawi and the Philippines. It was also exhibited at the White House and even featured on Shark Tank (the US version of Dragon's Den). More recent models can also be charged by USB and can charge mobile phones. Although the lamps were originally designed for emergencies, they are now also used by campers and people doing everyday outdoor activities. Learn more

-

In 2011 the city of Christchurch in New Zealand was severely damaged by an earthquake. Its cathedral, a major social and spiritual hub for the people of the city, was destroyed. The city invited Japanese ‘disaster architect’ Shigeru Ban to create a temporary cathedral that could also host concerts and civic events. Ban did this using cardboard and shipping containers as major building materials. Read more.

-

Ushahidi means ‘Testimony’ in Swahili. It is a software platform for use in emergency situations. It allows people to submit information about events that they have witnessed (for example, roads that are blocked or buildings that have collapsed). This allows people to avoid danger and helps emergency services to co-ordinate their work. It was inspired by the events following the 2007 election in Kenya, when civil unrest was not widely reported in mainstream media. It has since been used to help keep people safe during earthquakes, floods, conflict situations and even to document sexual harassment on the streets in Egypt. Learn more

-

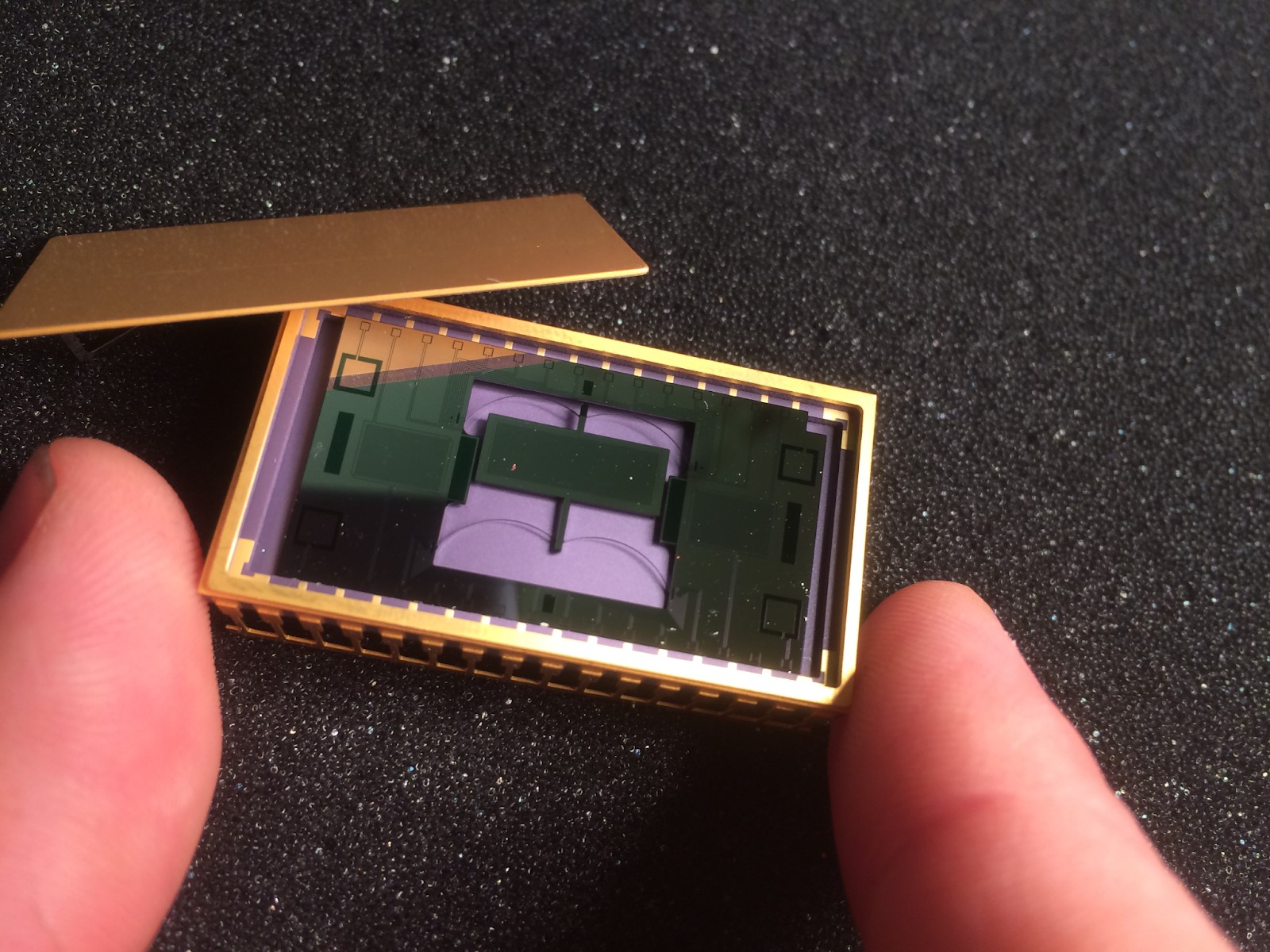

When you turn your phone sideways, how does it know to change the screen from portrait to landscape mode? Most modern smartphones contain small, cheap accelerometers: devices which can measure gravity to see which way up the phone is being held and adjust the screen so it’s the right way up. Scientists at the University of Glasgow have now adapted this technology by adding much smaller, more sensitive springs. They are made from silicon ten times thinner than a human hair – this allows the accelerometer to measure very slight changes in gravity. The new device, named ‘Wee-g’, is much cheaper and smaller than previous equipment used to measure gravity. It was used to measure the 2016 earthquake in Chile, and researchers hope that it can be placed around volcanoes as an early warning system. Learn more

When a severe weather event strikes, how do we know whether climate change was a factor? In this podcast, Dr Pete Walton explains how researchers use computer modelling to find out. They look not only at how extreme weather events are unfolding today, but what they would look like if there were no human-caused climate change factors. If there are significant differences between the two models, as there were with Storm Desmond in the UK in December 2015, climate change is likely to have been a contributing factor.

This knowledge can help us in two ways: by raising awareness that we need to control our impact on the climate, and by helping people who live in areas that are becoming more prone to extreme weather to plan and prepare.

How can we predict and survive natural disasters?

Technology might help us cope with the aftermath of natural disasters, but what can we do to predict them and prevent damage? Urban planners, computer scientists, journalists and even educators all have a role to play in keeping people and cities safe.

-

Catastrophic flooding in the city of Chennai, India, caused the deaths of more than 270 people in 2015. It also brought down the city’s electrical grid and international airport, and cost more than £1.5 billion. Professor Nikita Sud, Associate Professor of Development Studies at Oxford, argues that the flood was made worse by ‘a rampant disregard for town planning, and the basic principles of ecology and hydrology’. Issues included building an airport on the floodplain of the Adyar River (meaning that the river had no space to safely overflow when the rains came), and building over more than 273 hectares of wetland that would normally allow floodwaters to soak away safely. Read more

-

Satellite imaging can help scientists and governments to spot small changes to the surface of the earth or sea that might indicate a potential disaster in the making. Machine learning can enable computers to analyse satellite images faster than human beings can. Where major floods or droughts might take people by surprise in the past, data scientists like the team led by Dr Steven Reece at the Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science can help people and governments to prepare in time. Dr Reece explains their latest projects:

‘In Malaysia we will be working with government agencies to tackle flooding, oil pollution and illegal logging, all of which pose serious social and economic threats to Malaysian people.… In Ethiopia and Kenya [we focus] on creating an improved understanding of flood and drought risk, thus helping to build local people’s resilience to these natural disasters and alleviate poverty.’ The data gathered will also be used to help develop longer-term strategies to deal with droughts and floods, and to help farmers who would otherwise have little opportunity to insure their crops to access micro-insurance schemes. Read more

-

After an earthquake, a building might look fine on the outside – but how do we know that it hasn’t been damaged inside? Microscopic cracks inside a concrete structure might weaken it, and cause it to collapse unexpectedly the next time the ground is disturbed.

At the Oxford Department of Computer Science, Dr Orfeas Kypris recently discussed work on designing a set of transmitters to be embedded in new concrete buildings which will report on any structural damage in the concrete. This information can also be used to design better buildings in the future! Read more

-

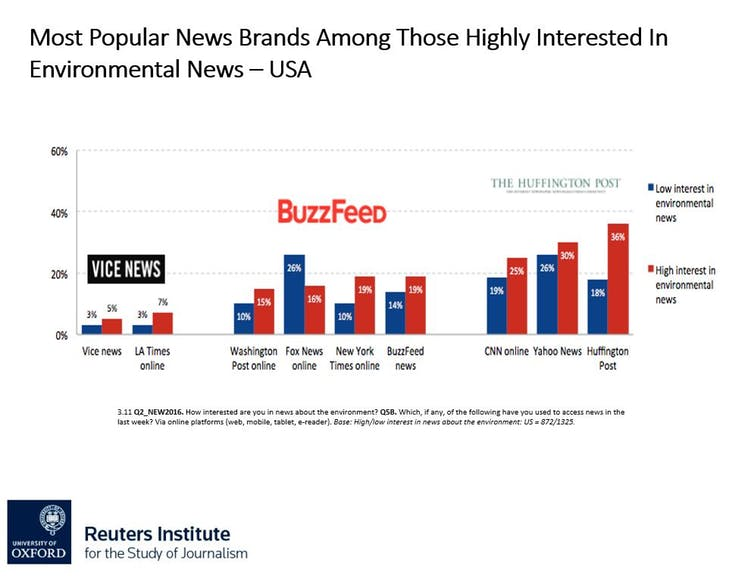

Climate change is an important factor in predicting and understanding natural disasters - but reporting on it can be challenging. As Dr James Painter, a researcher at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute of Journalism, points out, ‘TV editors often see climate change as too niche or too preachy,’ while ‘many audiences find the issue too remote, too frightening, or too consistently depressing.’ Funding for specialist science and environment reportage is also on the decline. However, a recent study by Dr Painter and colleagues looked at how ‘new media’ digital news and entertainment sites such as BuzzFeed, Vice News and the Huffington Post report on the environment. They found that these sites approached the issues in different ways, using strategies such as immersive video reporting, informal and irreverent language (eg. Buzzfeed’s list of ‘10 Adorable Animals that Climate Change is Killing Off’), and providing a positive, solution-based approach. The study found that ‘all three [websites] give editorial priority to environmental issues’, and were beneficial for the public debate about environmental issues because ‘they had found new ways of covering the ‘old’, sometimes boring, often remote, theme of climate change’. Read more

Climate change is an important factor in predicting and understanding natural disasters - but reporting on it can be challenging. As Dr James Painter, a researcher at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute of Journalism, points out, ‘TV editors often see climate change as too niche or too preachy,’ while ‘many audiences find the issue too remote, too frightening, or too consistently depressing.’ Funding for specialist science and environment reportage is also on the decline. However, a recent study by Dr Painter and colleagues looked at how ‘new media’ digital news and entertainment sites such as BuzzFeed, Vice News and the Huffington Post report on the environment. They found that these sites approached the issues in different ways, using strategies such as immersive video reporting, informal and irreverent language (eg. Buzzfeed’s list of ‘10 Adorable Animals that Climate Change is Killing Off’), and providing a positive, solution-based approach. The study found that ‘all three [websites] give editorial priority to environmental issues’, and were beneficial for the public debate about environmental issues because ‘they had found new ways of covering the ‘old’, sometimes boring, often remote, theme of climate change’. Read more -

How can you protect yourself against earthquakes if you don’t know what causes them or what effects they could have? Some people who live in earthquake areas don’t have access to formal education about the science behind them or good information about how to protect themselves, especially not in their own language. The Parsquake Project is a collaboration between researchers, engineers and teachers in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan and Europe. They create videos, classroom resources and activities to help people learn about what causes earthquakes, understand the dangers, and share their own stories and experiences. You can see an example video below, or check out the project.

Take this further: This video discusses earthquakes that occur at the boundaries between continental plates, but scientists have also been investigating earthquakes that happen within plates, which can be harder to predict and often very destructive. Read more

Could you survive a natural disaster?

Natural events and disasters have been part of our world for a long time, and there’s no doubt that they can be devastating for the people and animals that are caught up in them – just ask the dinosaurs! But over time we can study them and learn how they work. For example, charting cyclical effects such as ocean currents has helped us to gain more insight into how they interact with the atmosphere, and how this influences droughts and flooding.

Earth scientists have also been able to study the geological record to find out about the distant past of our planet, before human evolution, and study natural hazards from the distant history of the earth. It’s interesting to think about the effects that these events have had on the world and society – for example, would Europe be a different place today if more (or fewer) people had died in the 1918 Influenza Pandemic? And what would things be like for us mammals if the K-PG event hadn't caused a mass dinosaur extinction?

While natural disasters can have terrible consequences, the problems that they create have also driven people to use materials in new and interesting ways. These inventions can also go on to improve people’s everyday lives. For example, the LuminAID inflatable solar lamps inspired by the 2010 Haiti earthquake are now also purchased by people who go on camping trips, while the Ushahidi software platform has recently been used to monitor elections in Kenya, Nigeria and the USA as well as to track disaster situations.

Changes in our environment and rising population levels might affect the impact of natural disasters in the future. It’s important to research this because spotting patterns in when and where natural disasters occur helps people to prepare for them. As Dr Pete Walton discusses in the podcast above, even simple measures such as setting up a heatwave plan can save lives. Meanwhile, tracking changes in how often disaster events occur and how serious they are will give us more information about how the planet is changing, and what we need to do to stay safe.

As well as creating new inventions, we can change our behaviour in order to better manage natural disasters. Studies in international development can help leaders to make better policy decisions. Computer scientists and engineers can gather and analyse data in order to predict incidents such as droughts and building collapses before they occur, and track whether natural disasters are happening more often. And teachers and journalists can work to make sure that everyone has access to the information that they need to cope with natural disasters, in a format and language that are appropriate to them.

Source:

Source: