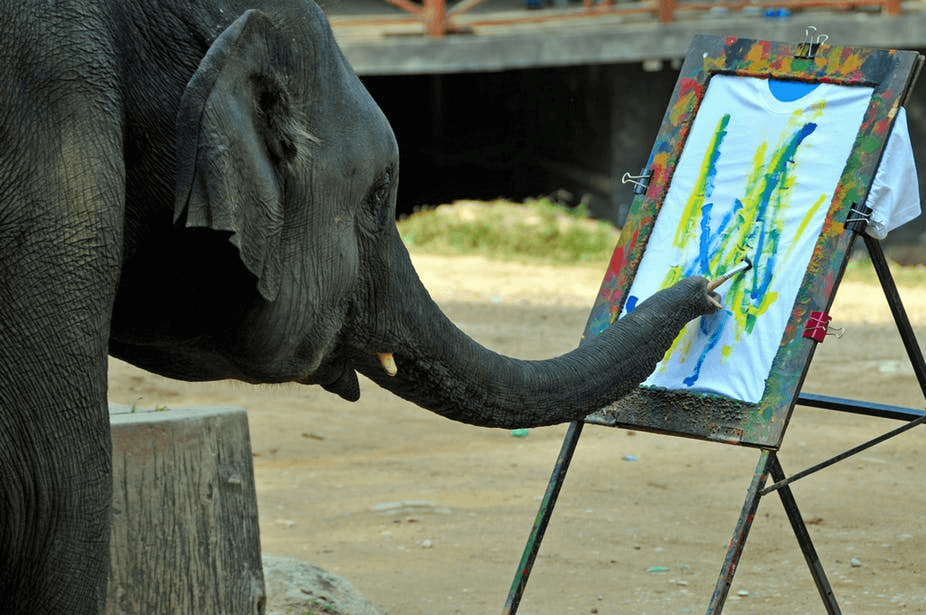

Don’t give up the day job, Nelly. Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA

In my time I have seen some pretty strange things parading as art – I still vividly remember the sawn-up sharks and cows in Damien Hirst’s Sensation Exhibition. Beauty and art I guess is in the eye of the beholder. What I consider to be art you may well think of as a pile of rubbish, and indeed it may actually be someone’s junk.

Anthropologists consider art to be a uniquely human activity in which a person produces something for the aesthetic appreciation of others. But human motives are seldom so simple. Modern-day artists are very aware of the commercial value of their product and of the fringe benefits of being successful artists such as fame and attracting members of the opposite or same sex. Art I suspect was never just for aesthetic appreciation.

This anthropologic definition of art seems to exclude the possibility that animals can be artists. For example, we might find male birds of paradise extremely beautiful but this is not art. Bird song is often described as music and the displays of some animals are described as dance. But do they qualify as art?

Although the song of many birds is improved by practice during the animal’s lifetime it is largely innate – the animal is not composing on a blank slate. And the same seems to apply to animal dances or constructions.

The intricately designed nests of the weaverbird would seem to be a work of art but is nothing more than an evolutionary pre-programmed design – and, of course, it was designed to hold eggs not for artistic appreciation.

Our descriptions suggest artistic qualities in these animals, but the reality suggests something much simpler. The dulcet tunes of my voice may sound beautiful to some, but they are the result of my environment and not any artistic composition.

Meet the animal artists

There are, however, cases of artistic creation in the animal kingdom that may meet the anthropologist’s requirements for something to be considered art. One such case is the song of the male lyrebird from central Australia.

The lyrebird does not learn its song from his father as is the case with most bird species. Instead it samples the song of birds from its habitat and puts these samples together in a continuous sequence, just as a DJ might rearrange snippets and loops of old records into a new song.

The aim of the male lyrebird is to create music that will attract females, which also seems to work for human musicians. When in captivity it has even been known for these birds to sample the sounds of human activity such as chainsaws cutting down trees or even human music played by loggers. Thus, the bird is producing non-innate “music” for the appreciation of others, in this case females of the same species.

Studies have shown that most bird song cannot be considered music, innately produced or not, because it does not follow human musical scales. I personally find this a weak argument as there are a great number of musical scales used by humans. What is noise to me maybe music to you.

Male bowerbirds make and decorate what is essentially a twig sculpture – bower – to impress females. Females pass by, inspecting these works of art – and the males stand in front of them hawking their artistic prowess.

Male bowerbirds use visual illusions that mess with perspective, just like the artist MC Escher. They create a courtyard of objects in front of their bower, the largest objects being placed further away creating a forced perspective that they are larger than they really are. If the female is impressed by the male’s artistic talents then she will mate with him. The theory being that great male artists possess good genes, which the female’s offspring will inherit. Once mated, the female will leave the male and head off to make her nest and rear her offspring alone.

There are of course captive animal artists such as pet cats or zoo-housed chimpanzees who are provided by humans with an opportunity to express themselves artistically. They may produce works like Jackson Pollock – but this is an induced, not a spontaneous activity and it is not clear if there is any artistic intent. Although the famous sign language chimpanzee Washoe would sometimes describe what her paintings represented.

Bower and lyrebirds provide just two animal examples from the wild of work that can be considered art in light of the human definition of the subject. Personally, I believe there are many more artists to be discovered in the animal kingdom.

But I, for one, would question this division between things that are beautiful or artistic. Surely what is important is that there is an aesthetic appreciation of them: whether they are a beautiful mountain that has been sculpted by glaciers, a sculpture made by bowerbirds or Michelangelo’s David. Personally, I appreciate the beauty in all three of these examples because they elicit in me the same emotional response of being in awe.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()