The 'Out in Oxford' project aims to celebrate diversity and highlight LGBTQ+ experiences. Each of the descriptions below were written by volunteers from Oxford's LGBTQ+ community and share the stories behind these remarkable items. Plus, the project logo above was designed by Jack Kearsley and Ren of Oxford's LGBTQ+ youth group., My Normal. To view the full trail, visit the Out in Oxford website.

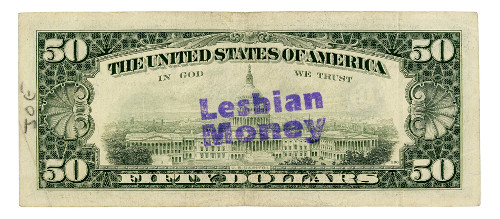

$50 US banknote counter-marked with the words ‘Lesbian Money’

Date: Late 20th century

Country of origin: United States of America

Location: Ashmolean Museum

The US gay and lesbian rights movements – which evolved throughout the 1970s towards the end of the 20th century – adopted many surprising and covert strategies of political protest and civil disobedience. One particular method of activism was to (illegally) stamp dollar bills with the slogans: ‘gay money’, ‘lesbian money’ and ‘queer $$$’. The circulation of the notes across the States draws on a long tradition of currency being defaced with political messages. As the notes are exchanged from hand to hand, they foster unexpected and intriguing encounters with the dissenting individual, who, in this case, stamped her money in purple – a colour broadly associated with 20th century women’s liberation movements – and the marginalised community of which she was a part. It is an understated, yet powerful, act of resistance, which makes it possible for lesbian voices, in particular, to be seen and heard.

By Adrienne Mortimer

Seated figure of the bodhisattva Guanyin

Date: 13th century

Country of origin: China

Location: Ashmolean Museum,

The image of the seated bodhisattva marks a transitional phase in the transformation of the male form of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara into the Chinese female deity Guanyin, the ‘Goddess of Mercy’. Avalokiteshvara was said to be the earthly manifestation of the Buddha Amitabha, whose figure can still be seen represented at the front of the headdress. Avalokiteshvara, often translated as "the Lord who looks upon the world with compassion", was said to be able to appear in 33 different physical forms, seven of these as a woman or young girl. It is thought that Avalokiteshvara, with Buddhism, was introduced into China around the 3rd century BC. From his introduction until the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) images of the bodhisattva were increasingly androgynous, incorporating both male and female characteristics. In China, from the 12th century, Avalokiteshvara is entirely represented as the female white robed Guanyin.

By G R Mills

Manju netsuke showing the female warrior Tomoe Gozen and Wada Yoshimori

Date: 19th century

Country of origin: Japan

Location: Ashmolean Museum

This netsuke (根付), a carved toggle used to attach purses to traditional Japanese dress, shows Tomoe Gozen (巴 御前) and her lover Wada Yoshimori (和田 義盛). While this beautiful example dates from the 19th century, Tomoe lived in the 12th century. Tomoe was known for extreme feminine beauty on the one hand and unparalleled physical, masculine strength and courage on the other. She undertook the most male of professions by becoming a samurai (侍). In some tales, she is also a female entertainer, highlighting this contrast even more.

Semi-fictionalised accounts of Tomoe’s life became popular along with other stories that play with the notion of gender as performative – decided by actions and not biological sex – such as Torikaebaya Monogatari (とりかへばや物語, ‘The Changelings). Many females across history have assumed elements of masculine dress, nomenclature or gender, for a variety of reasons. They have acted in contrast to the behaviour their cultures have expected for their biological sex, against a corresponding binary gender, which can be viewed as surprisingly modern.

By Victoria Sainsbury

Bust of Prince Henry Lubomirski (1777-1850) by Anne Damer (1748-1828)

Date: c. 1787

Country of origin: England, UK

Location: Ashmolean Museum

This bust is typical of Anne Damer’s neoclassical sculpture, praised by contemporaries for its simplicity and purity. By contrast, her wealthy and aristocratic circle gossiped about the impurity they saw in her relationships with other women. From 1776, when her unsuccessful marriage ended in her husband’s suicide, accusations about her lesbian relationships appeared in print. For the rest of her life, rumours about her kept re-surfacing. Her social position helped her endure these attacks, but they threatened her relationships with less aristocratic women, anxious about the impact on their reputations. Anne was deeply pained by the libels and gossip about her, but she never chose to live safely out of the limelight. She refused offers of marriage and she appeared on stage in private theatricals attended by the whole of London society. She took up sculpture, a masculine pursuit, and exhibited her work publicly, asserting her identity as an artist.

By Katie Hambrook

False beards

Date: 1936-37

Country of origin: Southern Angola

Location: Pitt Rivers Museum

Traditionally Kwanyama girls of marriageable age go through a five-day initiation ceremony called the efundula. Towards the end of the ceremony, the girls wear false beards and eyebrows to become ‘bridal boys’ who spend around 25 days living freely in the bush ‘as men’. During this period the girls assume ‘male’ gender attributes which are complemented by the ‘female’ behaviour of the men or future husbands. The false beard and eyebrows are part of the gender shifting of this ritual, with the girls’ dances mimicking the men, and the girls being well-armed and permitted to beat their future husbands. Any resulting pregnancies from this time are considered legitimate and result in marriage. The false beard is part of the elaborate costume that marks the culmination of her wanderings, the return to the village and the start of a new life in her husband’s home.

By AKE

Shiva and Parvati

Date: Probably late 19th century (collected before 1910)

Country of origin: India

Location: Pitt Rivers Museum

This object depicts the Hindu deities Shiva and Parvati as a couple. There are a variety of Hindu legends detailing the events leading to their eventual marriage, but a common theme throughout is that their courtship was not plain sailing. However, their marriage has since been viewed as a model relationship in Hinduism and there is a sense of equality implied between the two in this object as they are both of a similar size, seemingly two equal halves of a whole. Shiva and Parvati, combined, create the god Ardhanari (translated literally as “the Lord who is half woman”), a god containing both male and female elements, which challenges monotheistic gods who are traditionally wholly male. Ardhanari is a patron of hijras, a term which, in some South Asian countries like India and Pakistan, refers to people whose gender identity is not necessarily male or female. People in the West might consider them transgender, but many hijras don’t identify with that label. Some of these countries’ governments have now legally recognised hijras as a third gender, although they still face discrimination and are disproportionately vulnerable.

By Olivia Aarons